Wednesday, July 4, 2018

Head-Melting Heat Wave Edition: Short Takes on Short Stories

Posted by

Lisa C. Hayden

at

5:45 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Anna Berdichevskaya, Red Moscow perfume, Sergei Dovlatov, Sergei Nosov, short stories

Sunday, December 31, 2017

Happy New Year! & 2017 Highlights

In terms of the year in books, 2017 seems (logically enough, I suppose) to fit the pattern of the last couple of years: lots of work on translations plus a quality-not-quantity situation with my reading. This year, however, brought some unexpected travel and more books than I ever thought I’d receive in a year. A few highlights…

Two favorite books by authors new to me: Vladimir Medvedev’s Заххок (Zahhak), which I’ll be writing about soon, is the polyphonic novel set in Tajikistan that I’d been rooting for to win either the Yasnaya Polyana or Booker award. And then there’s Anna Kozlova’s F20 (previous post), which won the National Bestseller Award: F20 is harsh and graphic in depicting mental illness and societal problems. Its feels even more necessary to me a couple months after reading; it has really stuck with me.

|

| PEN book pile, with cat ear in foreground. |

Posted by

Lisa C. Hayden

at

8:05 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Anna Kozlova, Sergei Kuznetsov, Sergei Nosov, Vladimir Makanin, Vladimir Sorokin

Sunday, January 24, 2016

Abracadabra, Anyone?: Nosov’s Curly Brackets

Posted by

Lisa C. Hayden

at

7:53 PM

2

comments

![]()

Labels: contemporary fiction, Sergei Nosov

Sunday, July 12, 2015

Food Fetishists in (Post-)Perestroika Petersburg: Nosov’s Member of the Society

Posted by

Lisa C. Hayden

at

5:43 PM

1 comments

![]()

Labels: contemporary fiction, Sergei Nosov

Sunday, June 7, 2015

2015 NatsBest Goes to Nosov

Posted by

Lisa C. Hayden

at

5:23 PM

2

comments

![]()

Labels: contemporary fiction, National Bestseller, Sergei Nosov

Sunday, April 19, 2015

One Shortlist (NatsBest), One Long List (Big Book)

Last week was so packed with work that I came close to

missing the National Bestseller Award (NatsBest)

shortlist: thank goodness for some somnambulant scrolling on Facebook! To

make this a double-your-pleasure week, the Big Book Award’s long list

was released, too. Here are highlights:

- Sergei Nosov’s Фигурные скобки (Curly Brackets) (19 points): Described by fellow finalist Anna Matveeva as magical realism about a mathematician who goes from Moscow to Saint Petersburg for a conference of микромаг-s. I can’t tell you how much I appreciate that Matveeva Googled “congress of micromagicians”—that’s what the word looks like, though for some reason I like the sound of “microwizard” better—and found several thousand links to appearances by various sorts of magicians. Some English-language Googling brought up the term “micromagic,” a word I’d never heard, though of course I know very little about magic in general. Point of interest: according to Wikipedia, “micromentalism is mentalism performed in an intimate session.” I enjoyed one of Nosov’s books but abandoned another, and this one sounds just crazy enough that it might work. Apparently the 19 points Nosov’s book earned is a NatsBest record.

- Oleg Kashin’s Горби-дрим (Gorby-Dream) (6 points): Yes, a book about Gorbachev by a journalist.

- Anna Matveeva’s Девять девяностых (Nine from the Nineties) (6 points): Short stories. Some, including (apparently) this one, were written for Snob. I thought some of Matveeva’s stories in an earlier collection were very decent.

- Alexander Snegirev’s Вера (Vera, a name and noun that translates as Faith) (6 points): A short novel about a forty-year-old woman who is unmarried. Snegirev’s Facebook description, posted at the time of the NatsBest long list, includes words like dramatic, comic, erotic (a bit), and political (a little). I’m looking forward to reading it. Starting tonight.

- Vasilii Avchenko’s Кристалл в прозрачной оправе (Crystal in a Transparent Frame) (5 points): This book’s subtitle is “lyrical lectures about water and stones,” and Avchenko apparently covers many aspects of life in Vladivostok, including fish(ing), as in this excerpt.

- Tatyana Moskvina’s Жизнь советской девушки (Life of a Soviet Girl) (5 points): Apparently a memoir about life in Leningrad during the 1960s through 1980s, with lots of detail.

As for the Big Book’s long list, well, it is long, weighing in at 30 books, so I’ll just pick out a few points, though they’re probably the dullest points since they leave out the writers who are new to me: I’ve only read about half the writers on the list.

- Four authors are on the afore-mentioned NatBest shortlist, for the same books: Sergei Nosov, Anna Matveeva, Alexander Snegirev, and Tatyana Moskvina.

- There are several authors I’ve read in the past, beyond Nosov, Matveeva, and Snegirev: Elena Bochorishvili (Только ждать и смотреть/Just Wait and Watch), Alisa Ganieva (Жених и невеста/Bride and Groom), Andrei Gelasimov (Холод/Cold), Eduard Limonov (Дед. Роман нашего времени/Grandfather. A Novel of Our Time), Viktor Pelevin (Любовь к трем цукербринам/Love for Three Zuckerbrins), Dina Rubina (Русская канарейка/Russian Canary), Sergei Samsonov (Железная кость/Iron Bone), Roman Senchin (Зона затопления/Flood Zone), and Aleksei Slapovskii (Хроника № 13/Chronicle No. 13).

- There’s also one book I’m reading, albeit very slowly, in spurts: Guzel Yakhina’s debut book, Зулейха открывает глаза (Zuleikha Opens Her Eyes), a historical novel about a kulak woman who, in my reading, currently appears to be on her way to exile.

Posted by

Lisa C. Hayden

at

6:50 PM

1 comments

![]()

Labels: Aleksandr Snegirev, awards, Big Book Awards, National Bestseller, Sergei Nosov

Sunday, May 12, 2013

A Jumble: Two Books, One Coven, and Six Literary Award Finalists

I took a break last week after a rather bloody incident involving

a grater, a chunk of Pineland sharp

cheddar cheese, and a middle finger. Now that I’m back to full typing

capacity, despite an occasional twinge in the finger, here’s a jumble of a post

to get me caught up…

I’ll admit that last week I was more than happy to

procrastinate writing about Sergei

Nosov’s Грачи улетели (The Rooks Have Flown/Left/Gone): in keeping with the jumble theme, The Rooks is a nearly indescribable jumble

of characters, places, and motifs. Nosov tells the story of three old friends—a

teacher, a typewriter repairman and watchman, and a former flyswatter salesman

and would-be artist(e)—in three non-chronological sections. Much of the book is

set in St. Petersburg, which lends itself to some nice passages about changing

names and times. And references to Dostoevsky. And peeing off a bridge.

I thought The Rooks

worked particularly well when Nosov examined contemporary art—one of his characters

makes a wonderful trip to the Hermitage and stares in the abyss of Malevich’s glassed-in

Black Square—and the fine lines

between art and life. The section set in Germany, where the flyswatter salesman

and would-be artist lives for a time and hosts the other two for a painful visit,

felt less successful because it felt, simply, too long. Despite some structural

misgivings, Nosov won me over with atmosphere, love for St. Petersburg, and a tone

that avoids the cloying and preciousness thanks, in large part, to tart commentary

on contemporary art and culture. The epilogue contains developments that brought

varying degrees of surprise and showed how little we may know our friends and

literary characters. It also cemented my interpretation of the book’s title as

a reference to fall, playing off the name of Aleksei Savrasov’s painting of rooks

that have returned in spring.

|

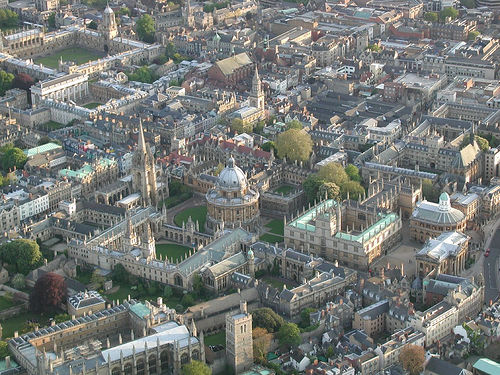

| Oxford from the air... must get up early enough to see city before coven... |

- Anne Applebaum: The Iron Curtain: The Crushing of Eastern Europe 1944-1956

- Masha Gessen: Man Without a Face: The Unlikely Rise of Vladimir Putin

- Thane Gustafson: Wheel of Fortune: The Battle for Oil and Fortune in Russia

- Donald J. Raleigh: Soviet Baby Boomers: An Oral History of Russia’s Post War Generation

- Karl Schlögel: Moscow, 1937

- Douglas Smith: Former People: The Last Days of Russia’s Aristocracy

Posted by

Lisa C. Hayden

at

6:23 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: events, Iurii Trifonov, literary translation, novellas, post-Soviet fiction, Sergei Nosov, soviet-era fiction