I wrote my last alphabet post (it’s here!) a little over two years ago, covering the letter Ч (Ch), which was productive but not rich with writers I considered real, true favorites. Today I present to you the letter Ш (Sh), which is highly productive in terms of the sheer number of writers whose surnames begin in Sh… though there aren’t many I yet consider serious favorites.

I’ll start with Varlam Shalamov since he’s probably the Sh writer I (hm, what word to choose?) revere the most, thanks to the beautiful and spare prose of his Колымские рассказы (Kolyma Tales), which document experiences in Soviet-era prison camp. Some years ago I took some good advice and read one Shalamov story each evening. I read him that way for several weeks; dozens of short stories in my nine-hundred-page book await me. Here’s a previous post (about cold and snow) where I mentioned that reading. I highly recommend Shalamov to all readers.

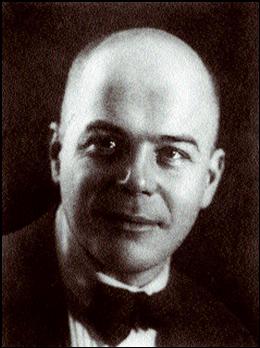

Things start to get much foggier after Shalamov so I’ll start with Viktor Shklovsky, whom I read in grad school, but have (unjustly) pretty much ignored for decades. I think I (probably?) read him first for literary theory – most likely “Искусство как приём” (here it is in English! “Art as Technique”) – and, since I enjoy literary theory, I’ve pecked away at his theoretical writings over the years. I even have a nice edition of Energy of Delusion: A Book on Plot, translated by Shushan Avagyan for Dalkey Archive Press, who gave me a copy of the book at BookExpo America. I should read it in full one of these days/years. I read Shklovsky’s Сентиментальное путешествие (Sentimental Journey) in full decades ago, though I’d be lying if I said I remember much beyond a quick summary: it contains his recollections about the Russian Revolution and Civil War. I’ve recently had thoughts of rereading it. I have much more work to do on Shklovsky! Particularly since I have yet to read Зоо, или Письма не о любви (Zoo, or Letters Not About Love, which Jennifer Wilson discusses here, in The New York Times), an embarrassing gap in my reading since I vowed to read it after finishing Alisa Ganieva’s dishy (as I put it) page-turner of a biography of Lily Brik… I wrote of the Shklovsky connection here. I’ll end by adding that I nearly forgot to mention that Shklovsky coined the term “остранение,” a word usually translated as “defamiliarization.” I love the word and what it describes.

And now to start on my stack of contemporary Sh writers’ books… Mikhail Shishkin has impressed me most in recent years with essays, both about Russia’s politics and invasion of Ukraine, and about writers. His lengthy piece called Бегун и корабль (The Runner and the Ship), about Vladimir Sharov, is particularly good – written about a beloved friend and his books – but I also loved reading his essay about Robert Walser, who is somehow terra incognita for me. As yet. Sharov is, of course, a Sh writer as well… and, as I’ve mentioned many times, he’s difficult for me to read, in large part because, sadly, I’m so biblically illiterate. (Foisting Sunday school on me was utterly counterproductive because I don’t like singing or memorizing. Reading the Bible itself during sermons on weeks when there was no Sunday school, however, was fun because I could read freely.) I’m still committed to putting lots more time into Sharov because I so enjoyed knowing him and still, despite not having known him very well, mourn his death because (as I’ve also written many times, including here) he was so otherworldly. Odd though it sounds, I still feel as if he simply couldn’t die, even physically. My strategy is still to restart my Sharov reading with his Будьте как дети (Be As Children), which I read and enjoyed nearly half of before I had to sample his other books to prepare for moderating an event… This article – “How Sharov’s Novels Are Made: The Rehearsals and Before & During” – written by my friend and colleague Oliver Ready, who has translated several of Sharov’s novels, looks like it will provide some of the hints (and pushing) that I need. Perhaps it will help others, too. Before & During, by the way, is the only Sharov novel I’ve finished as yet. I wrote about it here after Sharov won the Russian Booker in 2014 for Возвращение в Египет (Return to Egypt). I read the novel in Oliver’s translation, which Dedalus Books kindly sent to me; Dedalus has also sent copies of Oliver’s translations of Be As Children and The Rehearsals.

Vasily Shukshin, one of the most prominent (and, best, to my taste) “Village Prose” writers, is also in the Sh pile. I read his long and short stories every now and then and always seem to enjoy them, even when they’re sad as hell, like his Калина красная (The Red Snowball Tree), a novella that Shukshin didn’t just write. He also directed a film adaptation… and starred as the main character, a thief who’s been released from jail. On another note, yes, there are also a few women writers with Sh surnames. One of them, Ekaterina Sherga, wrote Подземный корабль (The Underground Ship), which I praised highly in 2013 (previous post). I believe Ship is Sherga’s only novel. There’s also Marietta Shaginyan, whose Месс-Менд (Mess-Mend) I read in 2005, finding it especially interesting as a 1920s period piece but a bit messy as a detective novel with nasty capitalists.

So! I still have plenty of reading ahead from letter-Ш writers like Shklovsky, Sharov, Shukshin, and Shalamov. I’d love to hope for more Sherga, too… I also have some unread Sh authors on the shelves: Ivan Shmelev, whose Солнце мертвых (The Sun of the Dead) Languagehat read last year (and called “grimly powerful”). It’s set in Crimea during wartime, in 1921. There’s also Roman Shmarakov’s Алкиной (Alcinous), which was a 2021 NOSE finalist – why not try a Russian novel set in the Roman Empire during the fourth century? And then there’s Vyacheslav Shishkov’s Угрюм-река, which Victor Terras, in A History of Russian Literature, calls Grim River, writing that it’s “about the colonization of Siberia.” The index of Terras’s book lists other Sh writers, including (of course) Mikhail Sholokhov, who didn’t endear himself to me much with Quiet Flows the Don decades ago… I’ll stop there and watch for thoughts on other letter-Ш writers!

Up Next: I have lots of catching up! Some of you have

written to me in recent months, asking when/if I’ll ever post regularly again. I

think (hope?) this is my start. I’m very grateful for readers’ kind notes,

gentle questions, and tact. I’m especially grateful to one of you for writing

to me last week, asking just the right questions at just the right time. Edit, March 13: After receiving a note from a worried friend, I want to add that I am fine. Blogging takes a fair bit of time; more than anything, I needed to spend more time on other things (particularly reading since I’ve had a lot of “required reading” of late) in recent months.

Disclaimers and Disclosures: The usual for knowing some of the contemporary writers (and their translators and publishers!) whom I’ve mentioned above. Thank you again to Dedalus for sending Oliver’s meticulous translations of Sharov’s novels, which I like reading along with the Russian originals.