I took a break last week after a rather bloody incident involving

a grater, a chunk of Pineland sharp

cheddar cheese, and a middle finger. Now that I’m back to full typing

capacity, despite an occasional twinge in the finger, here’s a jumble of a post

to get me caught up…

I’ll admit that last week I was more than happy to

procrastinate writing about Sergei

Nosov’s Грачи улетели (The Rooks Have Flown/Left/Gone): in keeping with the jumble theme, The Rooks is a nearly indescribable jumble

of characters, places, and motifs. Nosov tells the story of three old friends—a

teacher, a typewriter repairman and watchman, and a former flyswatter salesman

and would-be artist(e)—in three non-chronological sections. Much of the book is

set in St. Petersburg, which lends itself to some nice passages about changing

names and times. And references to Dostoevsky. And peeing off a bridge.

I thought The Rooks

worked particularly well when Nosov examined contemporary art—one of his characters

makes a wonderful trip to the Hermitage and stares in the abyss of Malevich’s glassed-in

Black Square—and the fine lines

between art and life. The section set in Germany, where the flyswatter salesman

and would-be artist lives for a time and hosts the other two for a painful visit,

felt less successful because it felt, simply, too long. Despite some structural

misgivings, Nosov won me over with atmosphere, love for St. Petersburg, and a tone

that avoids the cloying and preciousness thanks, in large part, to tart commentary

on contemporary art and culture. The epilogue contains developments that brought

varying degrees of surprise and showed how little we may know our friends and

literary characters. It also cemented my interpretation of the book’s title as

a reference to fall, playing off the name of Aleksei Savrasov’s painting of rooks

that have returned in spring.

Iurii Trifonov’s Обмен (The Exchange) is a lovely jumble, too, a long story about family

that blends past and present, private and public: Trifonov focuses on Viktor

Dmitriev, whose wife Lena wants to arrange an apartment exchange so they (and

their daughter) can live with Dmitriev’s mother, Ksenia, who is horribly ill. The

description

of The Exchange in Neil Cornwall

and Nicole Christian’s

Reference Guide to

Russian Literature is so good and detailed (even if it’s cut off!) that I’ll

just focus on impressions. I think what struck me most about

The Exchange was the grayness of

Dmitriev’s Soviet-era existence: his daily routine, his past affair with a

co-worker he thinks would have made a better wife than Lena, and, of course, disappointment.

Everything is beautifully observed and described though I find this sort of quiet—or

perhaps muted and repressed?—desperation even sadder than the harsher chernukha

of the post-Soviet era. I mean that as a statement of respect rather than a

criticism. Particularly since I have to think there’s a reason Trifonov chose

to include that cesspool.

|

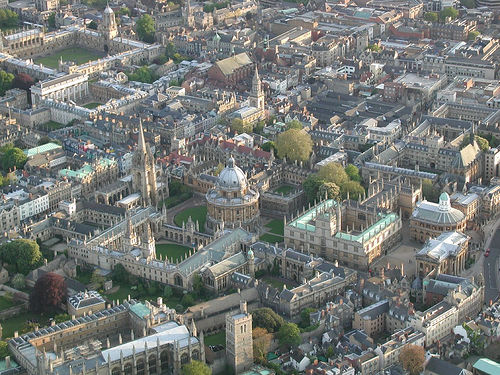

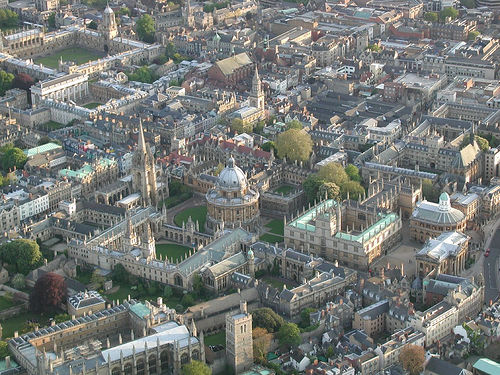

| Oxford from the air... must get up early enough to see city before coven... |

On another note, I’m very excited about

Translators’

Coven: Fresh Approaches to Literary Translation from Russian, a weekend

workshop I’ll be attending at St. Antony’s College, Oxford, next month. I’ll be

chairing a roundtable discussion about publishing and translations, and

speaking on a panel about translating dialogue in drama. The week after the

workshop, there will be a series of events about poetry translation at

Pushkin House in London. A huge thank

you to Oliver Ready and Robert Chandler for organizing all this. It’s a

wonderful chance to learn and get caught up with London-based colleagues. I can’t

wait!

Speaking of which… Pushkin House launched a new book award, the

Pushkin House Russian

Book Prize, “to further public understanding of the Russian-speaking world,

by encouraging and rewarding the very best non-fiction writing on Russia, and

promoting serious discussion on the issues raised.” I’m always vowing (and, generally,

failing) to read more (okay,

any!) book-length

nonfiction that complements my fiction reading, so the

Pushkin

House Russian Book Prize short list, which covers a wonderfully broad

assortment of topics, is a convenient place to start looking for candidates:

- Anne Applebaum: The Iron Curtain: The Crushing of Eastern

Europe 1944-1956

- Masha Gessen: Man Without a Face: The Unlikely Rise of

Vladimir Putin

- Thane Gustafson: Wheel of Fortune: The Battle for Oil and

Fortune in Russia

- Donald J. Raleigh:

Soviet Baby Boomers: An Oral History of

Russia’s Post War Generation

- Karl Schlögel: Moscow, 1937

- Douglas Smith: Former People: The Last Days of Russia’s

Aristocracy

Reading Levels for

Non-Native Readers of Russian: Medium for both the Nosov and Trifonov

books.

Up Next: A

novella (or two?) by Victor Pelevin.

0 comments:

Post a Comment