The core of Zakhar Prilepin’s novel The Black Monkey tells the story of the implosion of a contemporary Russian nuclear family—narrated

by a nameless father who tells of his nameless son, nameless daughter, and nameless

wife—that ends (almost) not with a bang but with the whimper of the letter ы. Prilepin extends his range beyond

the family by inserting set pieces from other times and places that show the

destruction of other families and, by extension, societies. One story, set in

Africa, includes an extreme example of in loco parentis, for child soldiers,

plus mentions of, apparently, celebrity mom Angelina Jolie.

Since Prilepin is, thank goodness, still Prilepin, he

juxtaposes episodes of misbehavior, stupidity, and cruelty, some quite nasty,

with tenderness, particularly his mixed-up narrator’s love for his small children. He

feeds them, reads to them, and worries about them. His descriptions of how they

unlock the apartment door when he rings, dragging a chair to the door so they

can reach the lock, felt especially sweet. Meanwhile, stories of child violence

and the father’s visits to his mistress and a prostitute led this reader to

wonder what will happen to these kids who chew gum like a meat grinder and eat

whatever hotdogs and pel’meni their nameless father puts on their plates…

The Black Monkey worked

best for me as an atmospheric novel, in large part because Prilepin combines realism

and abstraction, using language that has a quick, modern flow. The novel has

wonderfully mischievous humor that felt especially vivid after seeing and

hearing Prilepin at BookExpo America. And the book is a page-turner, albeit in

a strange way: I didn’t especially look forward to reading it but it held my

interest and kept me reading whenever I picked it up, despite a somewhat disjointed

structure that, I must admit, fits the topic. Most telling, though, is that The Black Monkey keeps knocking around

my poor skull; it dug its way into my subconscious.

For me, the highlight of The

Black Monkey was a brief scene where Nameless Dad reads to his children from a primer. The primer, though, is

unusual: the letters aren’t presented in alphabetical order. Instead,

they’re listed “будто в строгий

порядок букв упал камень и все рассыпал,” (“as if a rock fell into the

strict order and scattered everything”). The book presents “a,” the first

letter of the alphabet, then another vowel, “у,” which occurs in the second half of the alphabet and sounds like “oo.” Dad

plays with words for a bit with his kids then leaves them, saying he’s going

for cigarettes. He calls his mistress and plays more with the primer’s words as

he trots down the stairs and, literally, runs into his wife at the entrance to

the apartment building.

Nameless Dad calls his mistress, Alya, again from her

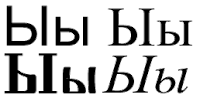

building’s entryway, pronouncing three vowel sounds, “Ы. У. О.” (“Y. U. O.”… though “ы” doesn’t sound like “y,” it

sounds like the tiny ы audio on this page). Alya asks, “Кто это?” (“Who is this?”),

addressing a Big Issue of Nameless Guy’s life that goes along with

the collapse of his family, the disordering of his alphabet (scary for a journalist),

and all that violence. I’d say the letter ы wins a place of (dis?)honor in the book: Nameless Dad’s last utterance

is a pained “Ы-ы-ы!” Accompanied

by thoughts of Hell.

Up next:

Alexander Ilichevsky’s Анархисты (The Anarchists), which I’m enjoying even

more than I’d hoped. And St. Petersburg Noir,

which is going to the beach with me this afternoon. And more 2012 Big Book

Award finalists… The Black Monkey is the

first I’ve read.