“Почти счастливый” (“Almost Happy”) is how the Russian news site lenta.ru titled a commentary about the death of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. The phrase “almost happy” turns up at the end of Один день Ивана Денисовича (One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich):

“Прошёл день, ничем не омрачённый, почти счастливый.”

“The day had passed, undarkened by anything, almost happy.”

Reading Michael T. Kaufman’s lengthy and balanced New York Times obituary of Solzhenitsyn reminded me of episodes I’d forgotten from Solzhenitsyn’s life: the hermit-like Cavendish years, the train trip across Russia, the spousal drama. I’d forgotten his crankiness, probably because I’ve focused for years on what I admire most: Solzhenitsyn’s willingness to ignore consequences and speak out against the Soviet regime.

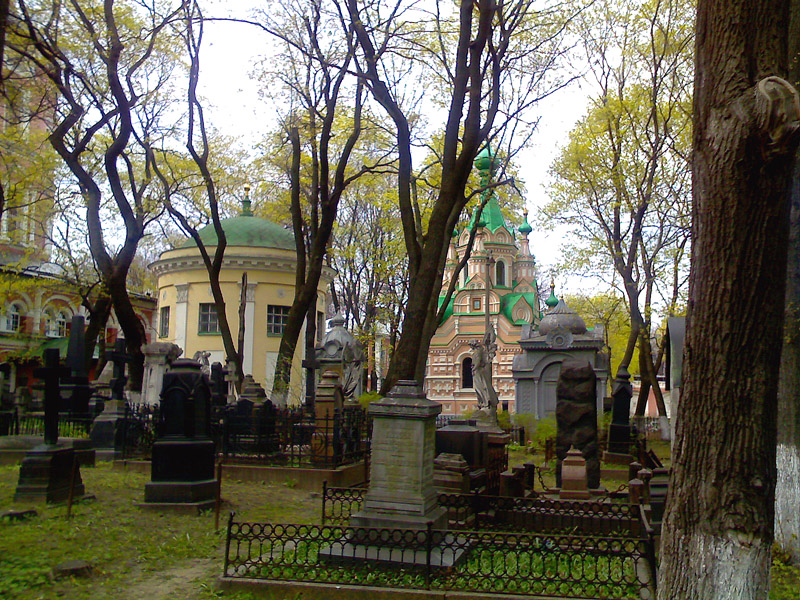

I also admire much of his fiction, particularly Раковый корпус (Cancer Ward), my favorite, thus far, of Solzhenitsyn’s works… though Ivan Denisovich has stood on my “To Read” shelf for months, awaiting a rereading. One book is compact, the other baggy, but both take place in enclosed places and address what it means to live and be human. In death, Solzhenitsyn will rest at Donskoi Monastery in Moscow. Donskoi Monastery and its cemetery were always modest, not a destination of dozens of tour buses, like Novodevichii Monastery and its famous graveyard. I lived near Donskoi Monastery during my first year in Moscow, and sometimes went to sweep old leaves off the grave of Mikhail Kheraskov, an eighteenth-century writer I studied in grad school.I always think of those days when I hear these lines from Aleksandr Gorodnitskii’s song “В Донском монастыре,” (“At the Donskoi Monastery”). Now when I hear them, my thoughts will broaden to remember Solzhenitsyn’s writings and imagine his grave, too, in a place I used to visit.

“Листопад в монастыре. (“The fall of leaves at the monastery.)Вот и осень, - здравствуй. (Here’s autumn – Hello.)

Спит в Донском монастыре (Sleeps at Donskoi Monastery)

Русское дворянство.” (The Russian nobility.”)

I'm still experiencing difficulty coping with Solzhenitsyn's death. And I was vastly disappointed to discover that so broad a number of my closest friends--all of them middle-aged and beyond--know so little of the man. Cranky or not, Solzhenitsyn indeed must've embodied a great deal of joy both within and without, for the empurpled face of his grandson with the burial at Donskoi was literally awash in tears of bitter anguish only the eyes of a genuinely devoted grandson can produce.

ReplyDeleteAn American who has long been intrigued with everything Russian, I have read Solzhenitsyn to the point that I had almost begun to think of him as a father-figure--indeed he strongly resembled my own father both physically and psychologically, and he was a decorated veteran of World War II.

I've heard media report that he is interred alongside the great Klyuchevsky and amidst bemedalled heroes of the Red Army and Great Patriotic War. For all the great leaders, heroes, and inventors I've known through my six decades, I can say with neither recrimination nor reservation that I think Solzhenitsyn the greatest singular example of any illuminary of whom I've yet read or heard. For me, Solzhenitsyn's name itself is directly and wholly synonymous with the word "freedom," and I'm absolutely aghast that his death received only scant international attention and for so short a period of time--when even the mere mention of his name once seemingly made the earth and heavens quake.

I failed in my first post to express thanks for your sharing of the photo of the peaceful interior of the Donskoi Monastery Cemetery garden. Wife and I plan a visit to the Moscow and Volga regions' next year, and I've recently included a stop at the Solzhenitsyn grave--so long as local authorities approve of such visitations.

ReplyDeleteA bit of news for you, given your photograph and stirring commentary on the man:

Six months ago, I penned a two-paged letter to Solzhenitsyn. I knew that he lived in Troitse-Lykovo at the time--though I was ignorant of his precise address--and my letter was directed first to the German magazine "Der Spiegel," then the great historian Dr. Zhores Medvedev (London), and ultimately, to Solzhenitsyn's Vremya publisher, Mrs. Alla Gladkova, in Moscow, at 41 Pyatnitskaya Ulitsa.

I wrote Solzhenitsyn knowing that he had suffered a debilitating stroke not so long ago, and that I would likely never receive a reply. Nevertheless, I asked the man to reveal the name of his closest wartime comrade, a handsome, sturdy, 50-something peasant-orderly known to Harrison Salisbury readers as "Dyodya Petya," or 'Grandfather Peter,' of Simbirsk.

With a trip planned for the Volga next year, I had hoped to uncover Peter's real name in that I might visit his grave in Ulyanovsk--if indeed he is buried there. With Solzhenitsyn's death, however, the secret of his orderly's identity will likely remain so. Sadly, I can now visit Solzhenitsyn himself.

Dear Anonymous,

ReplyDeleteThank you for your comment: I appreciate your writing about your reactions to Solzhenitsyn's death.

I, too, am often surprised at the lack of knowledge about Solzhenitsyn, but, unfortunately, I think many people forgot or ignored him in recent years because they believe he outlived his message. I don't share this view at all -- like Sakharov, he was a great example of someone who did not cave in to the Soviet regime -- but many Russians told me during the 1990s that they thought Sozhenitsyn's usefulness had passed.

I hope that you have a good trip to Russia next year. The cemetery at Donskoi Monastery is worth visiting, and I doubt there should be any difficulties getting in. Just be sure to check the opening hours before you go: they might be limited.

Again, thank you for your comment,

L.